Elephant Man Joseph Merrick was born on August 5th, 1862, at 50 Lee Street, Leicester, England. His parents were named as Joseph Rockley Merrick, who was a warehouseman, and Mary Jane Merrick, who suffered from a crippling condition. The family was completed by two younger siblings, brother William Arthur Merrick and sister Marian Eliza Merrick. Marian was also born a cripple.

Early Warning

Joseph was apparently free from any noticeable deformities when he was born, but at around the age of twenty-one months his lower-lip began to swell. This turned into a hard tumor in the right cheek of the baby Merrick, causing his mother obvious concern. However, she could not have foreseen the monstrous proportions which this development would eventually take. As he grew, so did the deformities. A bony lump appeared on the forehead, his skin started to become loose and rough, and his right arm and feet began to look peculiar. The most disturbing part for Mary Merrick was a long 'snout-like' lump of flesh that extended several inches from out of her son's upper-lip. Poor Joseph was to suffer further discomfort, when at the age of 3 he fell heavily, damaging his left hip. The family were too poor to afford proper treatment so the hip became diseased, which left him permanently lame.

Family Losses

In 1870, just before Christmas, Joseph's brother William fell seriously ill with scarlet fever. His condition rapidly deteriorated and within twenty-four hours he was dead. This laid a heavy burden on the shoulders of his suffering mother who had two crippled children and a shop to manage. In three years she too became seriously ill, this time with broncopneumonia. On Thursday May 19th, 1873, she died.

Early Warning

Joseph was apparently free from any noticeable deformities when he was born, but at around the age of twenty-one months his lower-lip began to swell. This turned into a hard tumor in the right cheek of the baby Merrick, causing his mother obvious concern. However, she could not have foreseen the monstrous proportions which this development would eventually take. As he grew, so did the deformities. A bony lump appeared on the forehead, his skin started to become loose and rough, and his right arm and feet began to look peculiar. The most disturbing part for Mary Merrick was a long 'snout-like' lump of flesh that extended several inches from out of her son's upper-lip. Poor Joseph was to suffer further discomfort, when at the age of 3 he fell heavily, damaging his left hip. The family were too poor to afford proper treatment so the hip became diseased, which left him permanently lame.

Family Losses

In 1870, just before Christmas, Joseph's brother William fell seriously ill with scarlet fever. His condition rapidly deteriorated and within twenty-four hours he was dead. This laid a heavy burden on the shoulders of his suffering mother who had two crippled children and a shop to manage. In three years she too became seriously ill, this time with broncopneumonia. On Thursday May 19th, 1873, she died.

It did not take his father long to remarry and by the end of 1874 Joseph had a new stepmother and step-siblings. To his dismay Joseph was rejected by his new family and was forced to look for work, eventually getting a job at a cigar factory. After two years he became a door-to-door hawker. When he spent all his wages on food for himself, he was severely beaten by his father and turned out onto the streets for good. He found refuge with his uncle Charles, a barber, the only member of his family who still gave him any consideration. But even this fell apart when Joseph couldn't keep up with his work and failed to have his hawking license renewed. Joseph knew his uncle couldn't afford to keep him on, so in the last days of 1879 he had no choice but to enter the Leicester Union Workhouse. Seeing his deformities the authorities had no hesitation in allowing him shelter. He was on his own from now on.

A Way Out

Life in the workhouse was a nightmare. After four years Joseph was desperate to find a way out. The only thing to have broken the monotony was an operation to remove the fleshy snout which had become too large. In his despair he wrote to a local showman, Sam Torr, asking to take him on as an exhibit. After a meeting, Mr Torr agreed to the request and Joseph joined him on a tour of the country. The 'Elephant Man' was born.

The arrangement with Torr eventually led to Joseph joining up with a man named Tom Norman, an exhibitor of London. It became a fruitful partnership for both, and for the first time in many years Joseph was given comfort and a decent wage to live on. He settled into exhibition life in a shop in the Whitechapel area, near the London Hospital. This location attracted a lot of interest from doctors who were keen to see the freak of nature. By now Merrick's condition had enhanced greatly: his head was huge, he had large boils and lumpy skin. His right arm was nothing more than an oversized club, and the same could be said about his legs and feet. All that was normal was his left arm, which had a feminine look to it.

One such doctor that came to see him was Frederick Treves. He arranged a private viewing for a small fee, and being horrified but intrigued by what he saw, managed to convince Tom Norman to allow Joseph an examination at the nearby hospital. Treves, a gifted young surgeon, examined him a few times, but the next request was turned down. Joseph was angered at being stripped naked and shown to Treves' colleagues. This was the last Treves would see of Joseph for some time.

End Of The Show

By 1885 public opinion was changing. Freakshows were no longer considered morally acceptable, and the police were obliged to close them down. This meant the end of the show for Joseph in Britain. While he had no problem exhibiting himself, the masses decided they knew better. It was degrading, a disgrace to human dignity, they said. So Joseph would have to give up his only means of making a decent wage, a time which had so far been the happiest period of his life. In a last attempt to continue working, he went to exhibit in Belgium with a Mr. Ferrari. It failed, the distaste for freakshows becoming as apparent in Europe as it had in Britain.

Elephant Man In June of 1886 Joseph was abandoned by Ferrari in Brussels. To compound his misery, Ferrari also stole his savings of 50 pounds. After pawning his few possessions, he managed to scrape together enough money to get back to London. A blow to Joseph came when he was refused passage on a boat by the appalled Captain, who said his horrid appearance would scare the passengers. He did eventually get to Britain, but by the time he arrived at Liverpool Street Station, London, he was mentally and physically exhausted. He collapsed, surrounded by curious onlookers, and handed a card to an assisting policeman. The card was that of Frederick Treves, The London Hospital.

A New Beginning

Joseph was initially put into one of the isolation rooms usually reserved for cases of contagious disease. With the help of Treves and the hospital staff he slowly regained his strength. Joseph suffered from an incurable condition so he would not be allowed to stay at the hospital after he had recovered as much as he was likely to. After five months it seemed that he would again be turned onto the streets. A publicity campaign was sparked on his behalf, including a famous letter to The Times by the hospital chairman Carl Gomm. This helped convince the hospital committee to accept Joseph as a permanent resident, a unique occurrence. The Elephant Man had a new home.

Two rooms of the hospital basement, known as Bedstead Square, were specially converted for Joseph's personal living space. The larger of the rooms became a bed-sitting room containing a table, chairs, fireplace, a specially built armchair, and a bed. The bed had to be set up in such a way as to account for Joseph's strange way of sleeping. Because his head was so big, it would cause suffocation for him to lie on his back, so he slept crouched over with his hands and head on his knees. The smaller room became a bathroom. No mirrors were allowed in either. Joseph was astonished with his new home, and spoke of his gratitude often. It was the stable environment he had been longing for all his life.

The Last Years

Only at the age of 23 could Joseph begin to enjoy life in a reasonably normal way. Treves kept up a close relationship with him, as both surgeon and friend. He learned to understand Joseph's obscured way of speaking and they enjoyed long conversations. It happened that beneath the horrific exterior, there lay an intelligent and sensitive young man who loved to read and to talk. To prevent him from feeling too isolated Treves would introduce him to friends and acquaintances. He met many people of high society, including members of the royal family, and exchanged letters with them. Among his possessions he could boast signed portraits of famous actress Madge Kendal, and Princess Alexandra. It became a cult among friends of the Princess to visit the Elephant Man in his hospital home. People would remark on what a nice character he had. There was not a trace of bitterness in him.

Joseph particularly enjoyed building models and baskets, which he would give to members of the hospital, and to friends. He had a wonderful time when he visited the theatre to watch a production of 'Puss in Boots', and in the later years he spent time on holiday in the country, walking through the fields and sitting in the woods. He also regularly attended service at the chapel.

His condition was all the time deteriorating, and it was known that he would not live much longer. His heart was weakening and his strength fading. He had to walk with a stick on account of his damaged hip. One thing that didn't fade, however, was his spirit. He remained content with his life, grateful for everything that had been done for him.

Joseph died suddenly on April 6th, 1890, at the age of 27. His body was discovered at around three o'clock when the house surgeon came to see him. He was lying across his bed, his neck having become dislocated by the immense weight of his head. Joseph had often spoken of wanting to sleep like normal people, and perhaps he was trying to do so. After his death his body was dissected and his bones still stand in the private museum at the London Hospital, along with casts made, and some of his possessions.

The Elephant Man

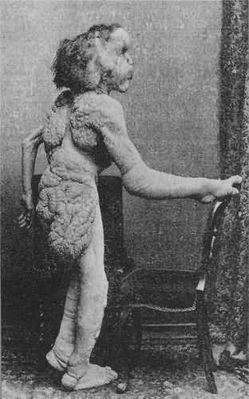

Joseph Merrick was described by many as the most degraded example of humanity they had ever seen. Almost all of his body was affected by deformity. His skull was a massive 32 inches in diameter and covered by huge lumps of bone and skin. The right arm was three times the size of the unaffected left, and basically useless. The legs and feet were like the right arm. All over his body, especially his torso, skin hung loose and had a rough feel to it. He was also short, only about 5'2" in height. In a perverse irony, the genitals remained entirely unaffected.

At the time a few theories were made as to what was wrong with Joseph, although no real conclusion has ever been made. An exaggerated case of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder of the skin, was considered a strong possibility. Proteus Syndrome, involving an overgrowth of bodily tissues and bone disorder, is a more recent theory. With the advancement of genetic science it should one day be possible to say conclusively what the problem was.

Frederick Treves went on to have one of the most distinguished careers in medical history, including saving the life of the king by operating on his appendix the day before he was to be crowned. There is no doubt that the arrival of the Elephant Man helped his career considerably, although this is not to say that Treves took advantage of Merrick, or that he didn't possess the talent to reach such heights. In his final book before he died, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, Treves wrote an account of his time with Merrick, although he chose to call him John rather than Joseph (this led to him being called John Merrick in the film The Elephant Man directed by David Lynch). In this book is an apt summary by Treves:

A Way Out

Life in the workhouse was a nightmare. After four years Joseph was desperate to find a way out. The only thing to have broken the monotony was an operation to remove the fleshy snout which had become too large. In his despair he wrote to a local showman, Sam Torr, asking to take him on as an exhibit. After a meeting, Mr Torr agreed to the request and Joseph joined him on a tour of the country. The 'Elephant Man' was born.

The arrangement with Torr eventually led to Joseph joining up with a man named Tom Norman, an exhibitor of London. It became a fruitful partnership for both, and for the first time in many years Joseph was given comfort and a decent wage to live on. He settled into exhibition life in a shop in the Whitechapel area, near the London Hospital. This location attracted a lot of interest from doctors who were keen to see the freak of nature. By now Merrick's condition had enhanced greatly: his head was huge, he had large boils and lumpy skin. His right arm was nothing more than an oversized club, and the same could be said about his legs and feet. All that was normal was his left arm, which had a feminine look to it.

One such doctor that came to see him was Frederick Treves. He arranged a private viewing for a small fee, and being horrified but intrigued by what he saw, managed to convince Tom Norman to allow Joseph an examination at the nearby hospital. Treves, a gifted young surgeon, examined him a few times, but the next request was turned down. Joseph was angered at being stripped naked and shown to Treves' colleagues. This was the last Treves would see of Joseph for some time.

End Of The Show

By 1885 public opinion was changing. Freakshows were no longer considered morally acceptable, and the police were obliged to close them down. This meant the end of the show for Joseph in Britain. While he had no problem exhibiting himself, the masses decided they knew better. It was degrading, a disgrace to human dignity, they said. So Joseph would have to give up his only means of making a decent wage, a time which had so far been the happiest period of his life. In a last attempt to continue working, he went to exhibit in Belgium with a Mr. Ferrari. It failed, the distaste for freakshows becoming as apparent in Europe as it had in Britain.

Elephant Man In June of 1886 Joseph was abandoned by Ferrari in Brussels. To compound his misery, Ferrari also stole his savings of 50 pounds. After pawning his few possessions, he managed to scrape together enough money to get back to London. A blow to Joseph came when he was refused passage on a boat by the appalled Captain, who said his horrid appearance would scare the passengers. He did eventually get to Britain, but by the time he arrived at Liverpool Street Station, London, he was mentally and physically exhausted. He collapsed, surrounded by curious onlookers, and handed a card to an assisting policeman. The card was that of Frederick Treves, The London Hospital.

A New Beginning

Joseph was initially put into one of the isolation rooms usually reserved for cases of contagious disease. With the help of Treves and the hospital staff he slowly regained his strength. Joseph suffered from an incurable condition so he would not be allowed to stay at the hospital after he had recovered as much as he was likely to. After five months it seemed that he would again be turned onto the streets. A publicity campaign was sparked on his behalf, including a famous letter to The Times by the hospital chairman Carl Gomm. This helped convince the hospital committee to accept Joseph as a permanent resident, a unique occurrence. The Elephant Man had a new home.

Two rooms of the hospital basement, known as Bedstead Square, were specially converted for Joseph's personal living space. The larger of the rooms became a bed-sitting room containing a table, chairs, fireplace, a specially built armchair, and a bed. The bed had to be set up in such a way as to account for Joseph's strange way of sleeping. Because his head was so big, it would cause suffocation for him to lie on his back, so he slept crouched over with his hands and head on his knees. The smaller room became a bathroom. No mirrors were allowed in either. Joseph was astonished with his new home, and spoke of his gratitude often. It was the stable environment he had been longing for all his life.

The Last Years

Only at the age of 23 could Joseph begin to enjoy life in a reasonably normal way. Treves kept up a close relationship with him, as both surgeon and friend. He learned to understand Joseph's obscured way of speaking and they enjoyed long conversations. It happened that beneath the horrific exterior, there lay an intelligent and sensitive young man who loved to read and to talk. To prevent him from feeling too isolated Treves would introduce him to friends and acquaintances. He met many people of high society, including members of the royal family, and exchanged letters with them. Among his possessions he could boast signed portraits of famous actress Madge Kendal, and Princess Alexandra. It became a cult among friends of the Princess to visit the Elephant Man in his hospital home. People would remark on what a nice character he had. There was not a trace of bitterness in him.

Joseph particularly enjoyed building models and baskets, which he would give to members of the hospital, and to friends. He had a wonderful time when he visited the theatre to watch a production of 'Puss in Boots', and in the later years he spent time on holiday in the country, walking through the fields and sitting in the woods. He also regularly attended service at the chapel.

His condition was all the time deteriorating, and it was known that he would not live much longer. His heart was weakening and his strength fading. He had to walk with a stick on account of his damaged hip. One thing that didn't fade, however, was his spirit. He remained content with his life, grateful for everything that had been done for him.

Joseph died suddenly on April 6th, 1890, at the age of 27. His body was discovered at around three o'clock when the house surgeon came to see him. He was lying across his bed, his neck having become dislocated by the immense weight of his head. Joseph had often spoken of wanting to sleep like normal people, and perhaps he was trying to do so. After his death his body was dissected and his bones still stand in the private museum at the London Hospital, along with casts made, and some of his possessions.

The Elephant Man

Joseph Merrick was described by many as the most degraded example of humanity they had ever seen. Almost all of his body was affected by deformity. His skull was a massive 32 inches in diameter and covered by huge lumps of bone and skin. The right arm was three times the size of the unaffected left, and basically useless. The legs and feet were like the right arm. All over his body, especially his torso, skin hung loose and had a rough feel to it. He was also short, only about 5'2" in height. In a perverse irony, the genitals remained entirely unaffected.

At the time a few theories were made as to what was wrong with Joseph, although no real conclusion has ever been made. An exaggerated case of neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder of the skin, was considered a strong possibility. Proteus Syndrome, involving an overgrowth of bodily tissues and bone disorder, is a more recent theory. With the advancement of genetic science it should one day be possible to say conclusively what the problem was.

Frederick Treves went on to have one of the most distinguished careers in medical history, including saving the life of the king by operating on his appendix the day before he was to be crowned. There is no doubt that the arrival of the Elephant Man helped his career considerably, although this is not to say that Treves took advantage of Merrick, or that he didn't possess the talent to reach such heights. In his final book before he died, The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences, Treves wrote an account of his time with Merrick, although he chose to call him John rather than Joseph (this led to him being called John Merrick in the film The Elephant Man directed by David Lynch). In this book is an apt summary by Treves:

Skull and skeleton of Joseph Merrick.

CT scan of Joseph Merrick's skull.

As a specimen of humanity, Merrick was ignoble and repulsive; but the spirit of Merrick, if it could have been in the form of the living, would assume the figure of an upstanding and heroic man, smooth browed and clean of limb, and with eyes that flashed undaunted courage.

No comments:

Post a Comment